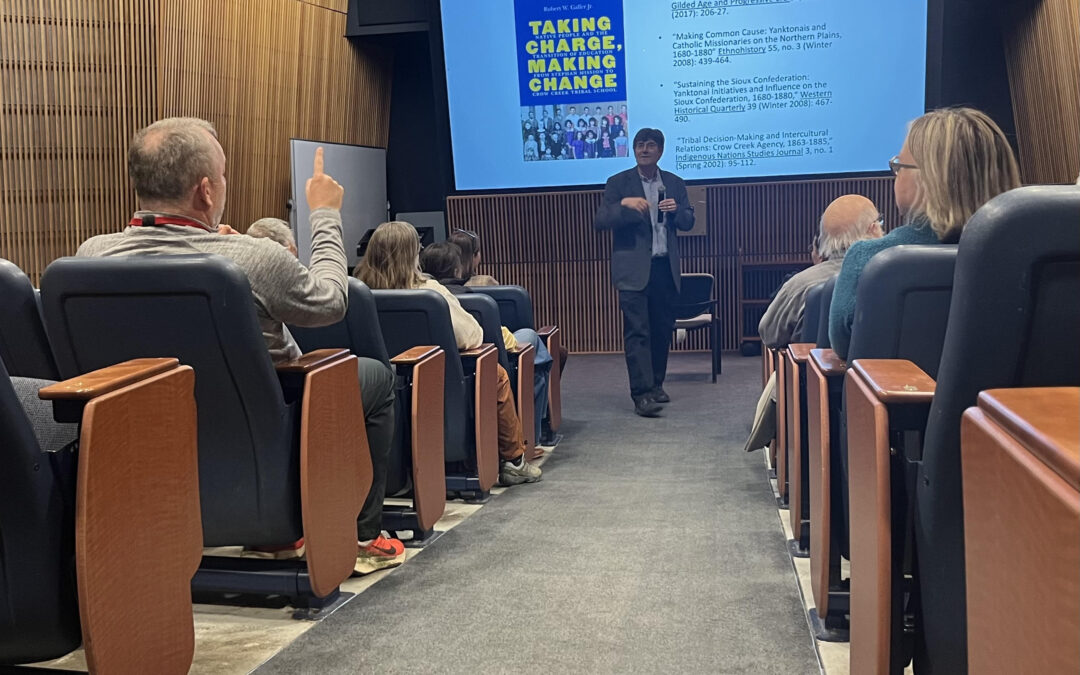

Photo: Dr. Robert W. Galler gives a speech on his book “Taking Charge, Making Change” to a crowd at St. Cloud State University

Story by Eli Holm. Photo by Eli Holm.

Contrary to when it takes place, history does change. Scholars from the field constantly reexamine narratives and, with every new generation, bring new approaches to telling the story of people and their world.

Scholars in the field of American Ethnic studies say that throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the narrative was of settler colonialism, slavery, patriarchy, and discrimination, making it a “top-down” narrative on the groups it explored.

However, as post-Civil Rights historians have argued, this narrative has limited the understanding of people into passive subjects written through the lens of the oppressive group, and a “bottom-up” turn in the field was necessary.

This is what Dr. Robert W. Galler, a Professor of History and American Indian Studies at St. Cloud State University, utilizes in his recently released debut book, “Taking Charge, Making Change: Native People and the Transition of Education from Stephan Mission to Crow Creek Tribal School.” It tells the story of how a 19th-century Catholic School originally built for Native American assimilation on the Crow Creek Reservation was shaped into the tribal school it is today.

Rather than telling a downstream version of history, Dr. Galler sought to tell the story from the perspective of the Native Americans who studied there and used their voice and their communal action to change the school. He points to his experiences teaching on the Navajo Nation Reservation in New Mexico and on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota as the places where he knew he would seek an education in Native Studies.

“I thought that if I was gonna teach in a Native Community, I felt I needed the context,” Galler said. “There’s no singular Native culture, no singular American Indian History, but there’s a lot of varied tribal and cultural dimensions to it, and I needed to learn that.”

Galler originally thought of continuing education as a context to be a more empathetic instructor, but it also gave him a lifelong passion for Native History. He got the opportunity to do a Ph.D in history at Western Michigan University, and because of his time on Pine Ridge (itself the subject of his master’s thesis), he knew he wanted to continue exploring reservations throughout South Dakota.

So, Galler turned his attention to Crow Creek, a Hunkpati Oyate Reservation cradled between hills on a bend in the Missouri River. It was back in the 90s when he started work on his dissertation, and the first outlines of “Taking Charge, Making Change” were created. In retrospect, he’s challenged the dissertation as being a more “top-down” narrative.

“It started as a vague timeline, just the nuts and bolts of where was the building put up, where did the money come from,” Galler said. “It was very much a traditional institutional history.”

But throughout the next 30+ years of research, he looked to fill in that timeline. Galler kept teaching at reservations, and he was reminded of what got him interested in Native History in the first place.

“I found I was more inspired by what I was experiencing in a community,” Galler said. “It was the experiences teaching on the reservation that got me to realize how little I know, which is probably the most important thing every teacher should learn, and from that, trying to understand further.”

It was this humility Galler took as he moved towards a bottom-up approach. Throughout his dissertation, the primary sources were record books, but in his years of research afterward, he turned to oral interviews, deepening the layers and challenging past presumptions.

“The story is often told as what happened to Indian people,” Galler said. “So, in writing this book, I tried to put native people in the subject of the sentence, not the predicate.”

The beginning chapters focus on Drifting Goose, the Hunkpati leader for 45 years. Galler notes his story because it exemplifies the larger headspace he found in the history of Crow Creek. He saw stories of Native people resisting assimilation and the larger settler colonial project, but he learned through Drifting Goose that the tribe was engaged in a much more complicated analysis of their situation.

“Drifiting Goose travels to Washington DC, I mean, these folks are engaged in their history,” Galler said. “They’re not just waiting for the next priest to come and build a school, or for federal officials to give them food, they’re in DC trying to self-sustain, but at a certain point, they realized that to be self-sustaining, they needed to develop alliances, which is a lesson many of us could learn. Nobodys making it on their own.”

To Galler, the story that was the most eye-opening was that of Ramon Roubideaux. Locals in the book praise him as the most famous graduate of Crow Creek. Roubideaux served in WWII, but upon returning from service, he was kicked out of a bar for being Indian. He planned to fight against the unfair treatment in court, but when he couldn’t find any lawyers to take his case, he got a law degree instead. Roubideaux went on to become a prominent lawyer for the American Indian Movement, which pushed for Native sovereignty in the 1970s.

“We always tend to think about history as one-dimensional characters, goody guy, evil person, nice person,” Galler said, speaking of how these stories influenced him. “And instead you’ve got people who do all kinds of different things, and putting these layers together transforms the story altogether. It’s like if you’re making soup, by putting in another can of tomatoes, there’s technically more soup, but it tastes different. It’s the same with history; you keep adding more layers, and you challenge the simple answers.”

Since Galler started “Taking Charge, Making Change” back in the ’90s, an entire history book’s worth of information has happened. Not to mention, Galler himself has lived more life than when he started. Since its release in January, Galler has been reflecting on himself and what he learned after spending so much time with Native Culture.

“When I was living on Pine Ridge, I participated in some of the ceremonies, and a key theme that all Americans could learn from them is humility,” Galler said. “When you’re going into a Sweat Lodge Ceremony, it’s all about saying ‘I am nothing,’ whereas the American and Western European traditions are more about like giving names and claiming things as knowledge, Indian Country is more about saying ‘I was taught that’ rather than ‘this is the answer,’ being the odd person out, being the minority in a group is powerful and I think many Americans are completely frightened by anything but their own, and therefore they critique anything but their own, instead of looking for what they have in common, and how can we piece that together.’”

For students of St. Cloud State University, “Taking Charge, Making Change” is available through the University Library in both print and ebook. To purchase “Taking Charge, Making Change,” you can find it through the University of Nebraska Publication Press. “Taking Charge, Making Change” is part of a larger series through the publication entitled “Indigenous Education.”

Recent Comments